ERYTHRÉE : LEVER LES BRAS POUR EXISTER. Mathieu ROUBY

LA CHINE ET SES VOISINS : ENTRE PARTENAIRE ET HÉGÉMON. Barthélémy COURMONT et Vivien LEMAIRE

L’ÉCRIVAIN et le SAVANT : COMPRENDRE LE BASCULEMENT EST-ASIATIQUE. Christophe GAUDIN

BRÉSIL 2022, CONJONCTURE ET FONDAMENTAUX. Par Hervé THÉRY

« PRESIDENCE ALLEMANDE DU CONSEIL DE L’UE : QUEL BILAN GEOPOLITIQUE ? " Par Paul MAURICE

LES ELECTIONS PRESIDENTIELLES AMÉRICAINES DE 2020 : UN RETOUR A LA NORMALE ? PAR CHRISTIAN MONTÈS

LES PRÉREQUIS D’UNE SOUVERAINETÉ ECONOMIQUE RETROUVÉE. Par Laurent IZARD

ÉTATS-UNIS : DEMANTELER LES POLICES ? PAR DIDIER COMBEAU

LE PARADOXE DE LA CONSOMMATION ET LA SORTIE DE CRISE EN CHINE. PAR J.R. CHAPONNIERE

CHINE. LES CHEMINS DE LA PUISSANCE

GUERRE ECONOMIQUE et STRATEGIE INDUSTRIELLE nationale, européenne. Intervention d’ A. MONTEBOURG

LES GRANDS PROJETS D’INFRASTRUCTURES DE TRANSPORT SONT-ILS FINIS ? R. Gerardi

LES ENTREPRISES FER DE LANCE DU TRUMPISME...

L’ELECTION D’UN POPULISTE à la tête des ETATS-UNIS. Eléments d’interprétation d’un géographe

Conférence d´Elie Cohen : Décrochage et rebond industriel (26 février 2015)

Conférence de Guillaume Duval : Made in Germany (12 décembre 2013)

POST-CONGRESS CHINA. New era for the country and for the world. Par Michel Aglietta et Guo Bai

samedi 2 juin 2018 Michel AGLIETTA Guo BAI

Dans cet article inédit, Michel Aglietta et Guo Bai vous proposent de comprendre la nouvelle trajectoire entreprise par la Chine, maintenant que ce pays a réalisée la plus grande partie de son rattrapage. Réformes internes bien sûr, autour de nouveaux enjeux (urbains, biens collectifs, réforme fiscale, inégalités et environnement...) mais aussi influence globale car la Chine est désormais aussi « dans le monde ». Avec la restauration économique de sa puissance, la Chine va également modifier les structures de l’économie mondiale (cf le projet de nouvelle Route de la soie).

Les travaux de Monsieur Aglietta se sont toujours appuyés sur l’idée force que l’économie ne peut être séparée de son environnement sociétal et sociopolitique dans une perspective historique longue. D’aucuns se rappelleront les modes de régulation mis en évidence par l’Ecole de la Régulation créée au milieu des années 70. Michel Aglietta est l’un de ces fondateurs avec Robert Boyer, André Orléan, Alain Lipietz... . Cette approche ambitieuse articule rapport salarial, formes de la concurrence, type d’insertion dans la DIT etc...

Nul doute que le développement de la Chine ne bouleverse les structures héritées du fordisme puis des années libérales en façonnant la mondialisation de demain.

Nous remercions vivement les deux auteurs de mettre leur expertise au service de nos lecteurs . P. L

POST-CONGRESS CHINA, New era for the country and for the world

Michel Aglietta [1] and Guo Bai [2]

Xi Jinping : “our civilization has developed in an unbroken line from ancient to modern times.”

Abstract

China is on a right track for undertaking ambitious reforms announced at the 19th congress. Growth strengthened in 2017 amidst fiscal tightening and prudent monetary policy. The shift from quantitative to qualitative growth is the coming “New Era”.

China enters a new era because the main contradiction that drives development has changed. The former contradiction was the scarcity of goods and services produced in the economy, which entailed poverty and required enforced industrialization to get people out of it. Since moderate prosperity is to be achieved, the main contradiction lies in the imbalances generated by past and present development.

Promoting the quality of growth aims first and foremost at reaching the technological frontier through innovation (digital economy, new energies and networks). It aims also at restructuring cities to achieve a harmonized urban/rural development in rethinking mobility. Migrants between countryside and cities should be able to carry their social rights.

To achieve its promise of prosperity in the socialist economy, the core reform on the demand side is centralizing social security, unifying retirement regimes and reforming the tax system to reduce the disparities between regions. Public goods must be delivered all over the countries through taxes and transfer mechanisms, so that less-favored regions are not forced to indulge in excessive indebtedness to provide the common goods and services that people are entitled to use.

The “New Era” has also a worldwide dimension. Recovering great power status under the full restoration of the Middle Empire for the 100th anniversary of the foundation of the People’s Republic of China is an ambition to be fulfilled in restructuring the world economy according to the mammoth project “One Belt, One Road” (OBOR). It intends to be a new concept of globalization.

OBOR opens opportunities to recipient countries that are infrastructure-constrained, because their lack of public goods is undermining their development. Conversely it is the right platform to push China’s soft power across Eurasia with strengthening economic linkages through trade, capital flows and construction deals. The OBOR initiative will succeed with Asian integration, since China will become the first world economic power before 2030. It is why OBOR is complemented by the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP).

China wants to develop economic, financial, technological and cultural relationships and cooperate politically to secure the global public goods on which our common security depends.

Introduction : what is the new era ?

In opening his report to the 19th congress of China’s Communist Party (CCP), President Xi Jinping has stressed national rejuvenation as the collective goal of the CCP to unite the people. The way to achieve it is in developing socialism with Chinese characteristics under the Party’s leadership.

Chinese characteristics mean that Chinese political philosophy does not believe in an ideal order. Neither does it believe in universal values. Chinese reform is embedded in long-run history. It is global, pluralistic, gradual and feeds on its own contradictions. What is perennial is the unitary sovereignty of the people. The criterion of successful achievement is entirely and exclusively practical.

Taking the long view to understand history, one can distinguish three eras : Mao has recreated the unity and independence of a poor and weak country. Industrialization was launched and pursued under terrible hardship. Deng has opened the way to prosperity in accepting to awaken private interests, promoting responsibility in exchanges and opening to the world. Xi asserts that moderate prosperity is on the way to be achieved at the conclusion of the 13th plan, on the eve of the celebration of the CCP’s 100th anniversary. However, the four decades necessary to achieve it have generated an unbalanced development in multiple dimensions of social life. Furthermore, China’s rejuvenation has a global dimension : recovering the power of the Middle Empire in the world community. Therefore the new era is divided into two periods : 2020-2035 to achieve the so-called socialist modernization ; after 2035 to the 100th anniversary of the People’s Republic of China in 2049 to reach social welfare within ecological civilization.

The goals of the directives of the 2013 third plenum of the CCP we studied in our 2014 policy brief (n°3, May 2014) to reach a socialist market economy persist. What is new is a clearer definition, better defined priority for qualitative growth and an evolution in two steps. Keeping in mind Xi’s grand design, we will structure this policy brief in two parts : first, balanced growth in China for the new era ; second, China and the world for an inclusive globalization. The questions we ask in the first part are the following : what is socialism with Chinese characteristics ? How can the Party represent the public interest ? The questions we ask in the second part are : what does China want to do to contribute to a new world order ? How does China collaborate with the rest of the world ?

I. Balanced growth for a new era

1. Past achievements and present outlook

In 1997, the year of the Asian crisis, GDP per capita in China was $782 ; in 2017 it was $8200. At the 15th Party Congress a strong government led by Premier Zhu Rongji, under the authority of CCP’s general secretary Jiang Zemin, took dramatic decisions to reform the economy that achieved astonishing results [3]. Effective leadership was critical. In the decade 1997-2007 China’s impact on the world economy was tremendous. In the years 2009-2017 the upswings in the world economy were largely driven by Chinese demand. Since 2013, under Xi Jipping, China’s government has managed the slowdown of the economy, curbed corruption and enhanced soft power abroad.

Pessimists about China, flourishing in Western establishment and media, have always been wrong in their dire predictions since Tiananmen event. They are unable to understand that the mix of State capitalism, managed markets and authoritarian rules is a recipe for long-term view, hence for breaking the tragedy of the horizons, while Western democracies, chiefly in Europe, have floundered for a long while in the mix of economic stagnation, slowdown in productivity, low productive investment and political discontent.

Since the 1970’s most Western people have been indoctrinated in a neo-liberal ideology that equates a market economy and a liberal political regime. However this is not what reasonable economic theory is teaching. Market efficiency demands that private property rights are secured and that innovation can thrive. These conditions are realized in China. There are both a very large private sector, a rising middle class and a widespread innovative spirit in the civil society. The middle class wants political stability, good governance and secure property rights. The party legitimacy rests on the attention to public goods. It is why the new era will be emphasizing qualitative growth. Therefore what is critical is effective leadership providing a long-term developmental view and a competent public administration. A dynamic economy is compatible with China’s authoritarian regime, as it is with competent democratic regimes, both empirically and theoretically. But it is not either with any authoritarian regime or any democratic one.

What Western critics always underrate is that the central authorities command a high degree of respect and support within the country. The large consensus stems from the ability of the development-oriented state to modernize, while ensuring political and macroeconomic stability. As pointed out by Zhang Weiwei, this way of governance originates from the Confucian tradition of strong, benevolent state, supported by meritocracy at every level of administration. In economic matters the guiding philosophy has nothing to do with any normative model of optimal equilibrium ; it is “seeking truth from facts”. Chinese characteristics in the development process mean a rejection of any shock therapy for the adoption of a pragmatic, trial-and-error approach to put people’s livelihood first. It has achieved what had never been undertaken before : a socialist market economy [4].

As we already pointed out in our former policy brief on the 13th five-year plan, Western scholars have totally misread the meaning of China’s unbalanced growth in the 1997-2017 period to moderate prosperity. Unbalanced growth has been the trajectory of the Asian regime of industrialization, already followed by Japan, Korea and Taiwan. Unbalanced growth reflects successful industrialization. Sustained high investment was necessary to shift hundreds of millions of workers from rural labor intensive activities to industrial capital intensive activities. The decline of consumption/GDP from 45% to 37% between 2000 and 2015 was not an impediment but the condition to achieve a continuous increase in per capita consumption over 20 years, much faster than any other major country.

Initial economic conditions are favorable for post-congress reforms. Growth strengthened in 2017 at 6.9% against 6.7% in 2016, benefiting from a widespread recovery in the world economy ; hence it was achieved amongst fiscal tightening and prudent monetary policy. Consumption expenditures confirmed that they have become the leading growth factor, with a contribution of 4.1% in the 6.9% GDP growth against 2.2% for investment and 0.6% for net exports [5]. Even so, private investment growth picked up to 6.0% in 2017 against 4.2% in 2016. The higher than expected GDP growth gives maneuver to rein in debt/GDP rise in order to maintain financial stability under a steady growth path.

Profits improved markedly in 2017 with reduction in overcapacities and supporting prices. Property prices calmed down in major cities with liquidity tightening and macro prudential measures. Therefore the government can safely consider slower growth in coming years under tighter regulation and deleveraging [6]. The average forecast of the international institutions is 6.5% GDP growth in 2018 and 6.3% in 2019, largely enough to achieve the goal set in 2011 of doubling the average real income per capita between 2010 and 2020 [7]. Indeed, to achieve the target, an average of 5% growth rate between 2018 and 2020 would be enough. Lower capital growth and a flat labor supply curve to 2030 leave total factor productivity (TFP) as the main driver of growth. This is the shift to qualitative growth on the supply side in the coming “New Era”.

The fundamental reorientation of the reform implies “the strengthening of the Communist Party’s comprehensive leadership”. It is why the Party’s Congress has been accompanied by institutional reform. The objective is to transform the overall political governance from “sector management”, a remnant of the planned economy, to “function management” to better coordinate separate ministries towards the goal of socialist modernization.

2. New Era : achieving socialist modernization to 2035

According to Xi’s report to the 19th congress, China enters a new era because the main contradiction that drives development has changed. The former contradiction was the scarcity of goods and services produced in the economy, which entailed poverty and required enforced industrialization to get people out of it. Since moderate prosperity is to be achieved, the main contradiction lies in the imbalances generated by past and present development. Therefore citizens’ wellbeing will be the principle guiding the socialist modernization to 2035. Supply side reforms are the means to achieve it in the economic sphere.

From March 5th to March 15th, the National People’s Congress (NPC) held its annual session, preceded by the meeting of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC) on March 3th. On March 5th Premier Li Keqiang presented the annual government working report. He announced a 6.5% growth target for 2018, equal to the average forecast of international institutions, an inflation target at 3% and 2.6% fiscal deficit, a conservative one from 3.7% in 2017. The authorities will be likely to set a range of targets between 6 and 6.5% until the end of the 13th plan, because it will be a transition period to help local governments adapt to the new era emphasizing growth quality. The targets will be adjusted so that the PBoC can maintain its prudent monetary policy stance to facilitate the deleveraging of the financial and corporate sectors.

Until 2035-40 the “affluent class”, meaning incomes equal or over $20.000, is expected to triple from 100 to 300 million people. Gradual achievement through supply side policies means keeping TFP-driven growth to 5% until 2025, then steady slowdown to 4% around 2035. Therefore the crucial question is the ability to spur innovation in a stable macroeconomic set up, so that TFP becomes the main factor of growth.

The myth that “China can’t innovate” is part of the perennial Western prejudices. However, indigenous innovation has been spurred since the 2006 Science and Technology Plan, then given prevalence in the 2013 industrial policy initiative known as the plan “Made in China 2025”. The overriding advantage is the huge market and the high competitive pressure to achieve economies of scale at home before venturing overseas, alike Japan in the 1960’s and 1970’s. State support and financial availability are strong complementary inputs.

In macroeconomic terms, using a naïve Cobb-Douglas production function, the shift from investment-driven to consumption-led growth means that Investment/GDP ratio adjusts from 45.7% in 2015 to 36.8% in 2025 and 33% in 2035. The growth of the capital stock will decline steadily from 9.5% in 2015 to 4% in 2035. Under constant structural unemployment rate and moderate increase in the participation rate, the trend in labor growth will be about flat from 2020 to 2030, then decreases at 0.2% annual rate between 2030 and 2035. Under these assumptions, potential GDP growth could reach 5% in 2025 and 4% in 2035. With this scenario and the assumption that the US will grow optimistically at 2.5% to 2035, the two countries will reach similar size [8].

The assumption for TFP growth in this tentative scenario is conservative. The upgrading process of the productive structure based upon the deployment of the digital economy might justify a higher TFP growth. The potential to improve over the long run is great with momentum Fintech, IT, e-commerce, high speed railways and new energy, all making up the strategic industries prioritized in the 2025 industrial policy objective.

TFP growth could also come from improvements of corporate governance in SOEs through SOE reform to eliminate inefficient firms and correct the misallocation of capital and labor in the economy. Productivity growth beyond normal might increase potential GDP growth 1% more to 2025.

Therefore promoting the quality of growth aims first and foremost at reaching the technological frontier through innovation (digital economy, new energies and networks). It aims also at restructuring cities to achieve a harmonized urban/rural development in rethinking mobility. Migrants between countryside and cities should be able to carry their social rights.

To achieve its promise of prosperity in the socialist economy, the core reform on the demand side is centralizing social security, unifying retirement regimes and reforming the tax system to reduce the disparities between regions. Public goods must be delivered all over the countries through taxes and transfer mechanisms, so that less-favored regions are not forced to indulge in excessive indebtedness to provide the common goods and services that people are entitled to use.

Democratic legitimacy with Chinese characteristics is expressed by what the Party has achieved for the people. The question of political legitimacy is less : what are the formal rights that define a democratic regime ? And more : what has been done with power ? Democracy is inseparable from inclusiveness since, according to Rawls, what counts are real conditions of liberty and that poverty is deprivation of liberty. Therefore respecting the law implies a relentless fight against corruption.

3. Digital economy : the fulcrum of a new growth regime

Innovation has spread at an astonishing speed in the last few years. Indeed the top three Internet companies in the world are American (Google, Amazon and Facebook). However Alibaba is fourth and Tencent is fifth. Moreover in the 10th top ones, each of the two countries has five. According to the Boston Consulting Group, amongst the 221 unicorns [9] existing in the world, 29% are already Chinese [10]. Chinese unicorns are catching up fast because startups take 4 years to reach the unicorn status, while American ones take 7 years. The combined market capitalization of American unicorns is still larger because The US has 112 unicorns while China has 63 for the time being. However, if the growth in China, both in number and market capitalization, is going on for some time, its market capitalization would overtake soon its US counterparts.

What are the driving forces in the outstanding development of China’s high tech industry that will make China the leading global force in the digital era ? Indeed, China is not only expanding its own market at an amazing speed. It is also shaping the global landscape and inspiring entrepreneurship in investing worldwide in digital technologies, creating a virtuous circle because it is also the world’s leading adopter [11]. The momentum triggers an intense creative destruction process on a larger scale in China for two reasons. First the digital industries draw advantage from the inefficiencies of traditional industries ; second the potential for commercialization is massive because the consumer demand for digitalization is so intense. The interactive dynamic between supply and demand contributes to the increase in total TFP.

According to McKinsey’s researchers there are three moving forces : the rapid commercialization of business models on the demand side, thanks to the large and young consumer market ; the broad digital ecosystem on the supply side that is much wider than the digital giants ; the government backing as investor and consumer of digital technologies. Therefore China is generating waves of digital innovations and entrepreneurial activities. The BAT (Baidu, Alibaba, Tencent) have been building a digital ecosystem proliferating beyond them. Alipay and We Chat offer super apps that give consumers a broad coverage about services and social interactions.

In 2006 China accounted for less than 1% of the value of worldwide transactions in e- commerce ; in 2016 it was 40%. All in all, there were 731 million Internet users against 343 million in EU and 262 million in US. The penetration of mobile payments has been tremendous. 68% of Internet users make mobile payments against 15% in the US.

On the supply side China’s venture capital is focused on digital investment. It has increased from $ 12bns (6% of world total) in 2011-13 to $77bns (19% of world total) in 2014-16. The main types of investments are big data, artificial intelligence and Fintech.

Going deeper into the interactions that link production processes to consumer demand, the research gathered in the McKinsey report exhibits three processes : disintermediation, disaggregation and dematerialization.

For instance, in providing mobility, disintermediation enables carmakers to reach consumers directly, while disaggregation lowers the demand for new car sales in substituting shared mobility devices. In health care provisions, disintermediation helps address chronic diseases via the Internet of Things and artificial intelligence. Disaggregation can reduce dramatically health care expenditures in making diagnosis with use of big data and 3-D printing. In freight and logistics, disintermediation can address industry fragmentation between small truck companies with real time matching platforms, while disaggregation can enable flexible capacity through crowd funding delivery. Finally dematerialization changes processes and products from physical to virtual, enabling consumers to get products that can be dematerialized anywhere at any time.

In China government policies gives a big boost to the digital economy in implementing the 2025 industrial China plan. The government is creating a market to frontier technologies in robotics and artificial intelligence by backing long-term investment in innovative companies and by expanding the infrastructure of the digital ecosystem. The government is also promoting competition to fuel innovation through low entry barriers for new firms. Finally and most importantly the government has the duty to manage labor markets during the digital disruption to 2030-2035. The shocks are manageable because the long view of the stable government makes it possible to make an effective program to smooth the transition as much as possible. The government must support lifelong learning and reform education to help people acquire the right skills. It must also improve job-deployment programs to enhance labor mobility.

4. Sustainable growth : matching digital economy and energy transition

Energy geopolitics has long been dominated by the fight against scarcity, since oil and gas are not available everywhere. The US has long maintained its hegemony in alliance with the feudal powers in the Middle East. The oncoming imperative energy transition to create a low- carbon energy system worldwide is the most powerful force that will transform the capitalist growth model. As Francis O’Sullivan (MIT Energy Initiative) claims, we are moving from a world where the value of the energy is embedded in the resource to another where technology is the resource”. Getting rid of the rentiers for a better world is what Keynes advocated long ago. China is aiming at leading this revolution to contribute at a new world energy order.

Building an ecological civilization in mid-century is a goal asserted by the 19th party congress. China’s growing middle class is demanding a cleaner environment anyway. Moreover the costs of industrialization have been huge. They are an extreme evidence of the “imbalances” [12]. 1.5million deaths a year are attributed to air and water pollution. 116 cities have fine-particulate concentration over five times the sage level set by the World Health Organization (WHO). GHG emissions tripled between 2000 and 2014. The Environmental Performance Index (EPI) ranked China 109° out of 180 countries in 2016.

Therefore there is a long way on. A new book on the geopolitics of renewables argues that the main constraint will shift from scarcity to variability, so that Grid Politics will replace Pipeline Politics [13]. China is firmly committed to clean energy and has already generated an impressive array of clean-energy entrepreneurs. The boost from the state through subsidies, policy targets and manufacturing incentives has paid out $132bn in 2017 alone according to Bloomberg new Energy Finance. It was more than US and EU combined. The International Energy Agency (IEA) reports that China has built a third of the world’s wind power, a quarter of its solar capacity and that it has sold more electric vehicles than the rest of the world [14].

This effort was guided by plans established from 2013 to 2016 to reduce air, soil and water pollution has improved the situation. Those plans amount to the world’s largest environmental cleanup effort. However the contradiction between economic and environmental goals has not been solved yet. It is what post-congress policies are expected to achieve in the long run. It is what green development as a linchpin of the quality of growth is about. The hypothesis is that “Going Green” in new products, technologies and investments to decouple from GHG emissions and environmental damages is itself a source of growth.

The macroeconomic reform implemented in the 13th 5-year Plan has already reduced the energy intensity of growth. The official target in the Plan is a reduction of 40 to 45% by 2020 below the 2005 level. This is crucial for boosting productivity and abating air pollution in lowering energy demand per unit of GDP. Substituting away from coal as an energy source is key for environmental sustainability both in GHG emissions and local air pollutants. The change in energy mix will stimulate the development of innovative growth industries. In primary energy the objective for the share of non-fossil fuel is 15% by 2020 and 30% by 2030 from 10% in 2013.

China’s target is absolute peak emissions in 2030 at the latest. What remains uncertain is the peaking level, the actual peaking year and the post-peak trajectory. Drawing from an in-depth study by the New Climate Economy (NCE) of the Global Commission on the Economy and Climate (GCEC), Fergus Green and Nicolas Stern are optimistic [15].

The NCE built and compared two scenarios : continued vs. accelerated emissions reduction. Both scenarios assumed the same average GDP growth rate : 7.3% in 2010-2020 and 4.8% in 2020-2030. Table 1 summarizes the results.

According to UNCPCC a reasonable global benchmark for 2030 would be 35GTCO2eq. If China’s emission are at 14GT, it will still take 40% of the carbon space. Green and Stern point out that 12 GTCO2eq should be an upper limit for China in 2030 and a target of 10 would better avoid the risk of an average temperature substantially above 2°C in the 2nd half of the century. In that case the emissions peak will be reached earlier than 2030 at a level lower than projected in the NCE study.

In pursuing the energy transition at a lightning speed, China is able to produce more of its own energy and reduce its reliance on fuel imports. Furthermore, in developing clean-energy technologies, China provides an impetus to inclusive and sustainable economic growth for the New Normal. Indeed, to eradicate poverty entirely and to go on increasing real wages fast, productivity gains must be found in high value-added, innovation-intensive sectors. Handling environment damages and fighting climate change resolutely is one best way to do it. It can be done in combining three ways : transforming traditional sectors with energy-efficient investments ; expanding energy-green industries with renewable energy investments, developing services via restructuring urbanization to smart cities.

Table 1. Comparing continued/accelerated scenarios.

| Variables | Continued reduction | Accelerated reduction | |||

| 2010 | 2020 | 2030 | 2020 | 2030 | |

| Total energy consumption (bns tons of ≈ coal) |

3.25 | 4.92 | 6.25 | 4.75 | 5.9 |

| Energy intensity of GDP (2010=100) | 100 | 73.4 | 54.6 | 70.6 | 51.6 |

| CO2 emissions from energy (GT°) | 7.25 | 10.4 | 12.7 | 9.68 | 10.6 |

| Proportion of non-fossil energy (%) | 8.6 | 14.5 | 20 | 15 | 23 |

| Total GHG emissions (GT CO2eq) | 9.4 | 13.5 | 16.5 | 12.6 | 13.8 |

Source : GCEC( 2014), Table 4.4, p.82. Results assume growth averaging 7.31% on 2010 -2020 and 4.77% on 2020-2030. They are based on the NCE China study : “Middle Economic Growth Scenario”.

How is it possible to achieve rapid emissions reductions post-peak ? City and energy reforms must be concerted in mixing clean innovations, green financing and fiscal reform.

In cities, urban planning is crucial for the long-term path dependency it creates. City planning must be based on compact models of urbanization, with cities linked in a modular system by high-speed railways supporting mass transit and a range of interconnected means of local mobility. Changing commuters’ transport system behavior on the demand side and electrification of the transport system on the supply side have a high potential of GHG emissions abatement. Road transport will also be overhauled, combining electric, hybrid and fuel cell vehicles using low-carbon bio fuel. It can make huge differences on local pollution. Urban planning requires reforms to city-level fiscal and governance arrangements.

In energy efficiency work is still to be done. To displace coal usage, non-coal primary sources will be scaled up. Gas and hydroelectricity will be developed in the medium term, while other renewables and nuclear will be expanded at an accelerating pace. Gas will be used in the medium term in many activities to replace coal. It will be mainly supplied from Russia and Central Asia through pipelines. Nonetheless, under the imperative of energy security, shale gas can take the lead in the medium term as a substitute to coal and a backup of renewables.

Most important will be the grid system management between variable and non-variable energy sources. Furthermore, the opportunity of storage in the future will come from lower cost battery linked to large-scale electric vehicle expansion. It is where digital devices will be most useful. China’s leap forward in digital technologies will make renewable energy storage and distribution more competitive.

5. Inequalities and inclusiveness in China

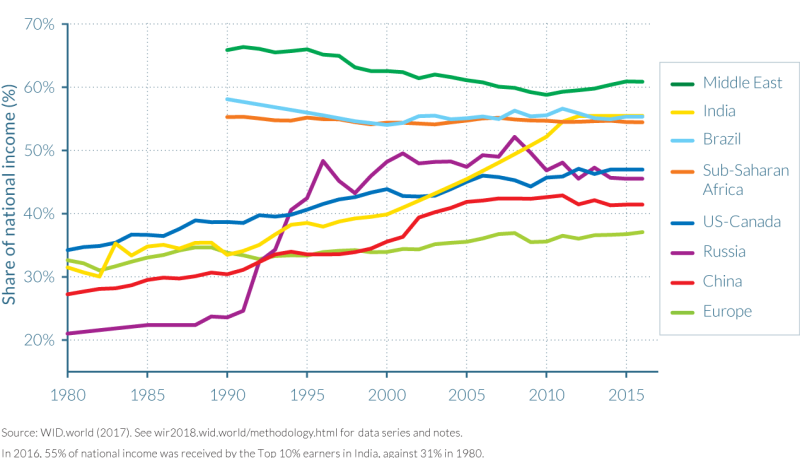

An advanced team commissioned by the UN was gathered to compare the income distribution in China, in advanced countries and in other regions of the world from 1980 onwards [16]. The measure of inequality is presented as the share of the 10% top earners (figure 1). On both measures, inequality in China in later years is higher than in Europe but much less than anywhere else in the world, including the US and Canada. In 2016 the 10% top earners captured 37% of national income in Europe, 41% in China, 46% in Russia, 47% in US and Canada. It reached 54% in Sub Saharan Africa, 55% in Brazil and India and an extravagant 61% in the Middle East. The profile in Russia is very interesting. Until the breakdown of the USSR, it was by far the less unequal country worldwide, followed by China. Then the share of the 10% top income jumped incredibly, doubling from 25 to 50% of GDP from 1992 to the Russian crisis of 1998 in the Eltsine era, when the oligarchs carved up state property alike vultures. In reinstating state authority, Poutine turned down and then stabilized the inequality curve, albeit at an elevated level.

Measured by the share of the top 10% income, inequality in China increased substantially from 1998 to 2006, levelled off from 2006 to 2012, then has declined slightly with the catching up of the minimum wage decided in the 12th five-year plan starting in 2010 and with the fast rise in average wage in the 12th and 13th plans.

As pointed out here above, an emerging middle class in China is under way. The recent rate of wage growth has been high and social benefits have improved. Increased wages should result in consumer demand for better services. It should also lift the prices of non-traded related to traded goods, raising the profit margin of firms in the services and consumer goods sectors. This might in turn generate demand for labor to substitute for the reduction in production capacity in oversized industrial sectors.

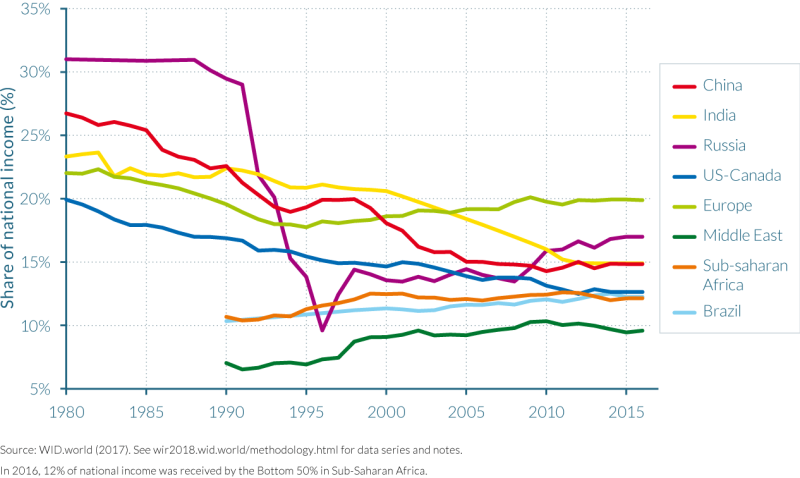

There is no surprise that the bottom 50% income on figure 2 shows inverted profiles compared to figure 1. However both curves can be misleading if the overall growth performance of the economy and that of different income groups in terms of real income growth is not taken account of. Table 2 shows off the widening gap in income structures as well as their growth performance over 1980-2016.

The table underlines China’s impressive performance. It was already mentioned that the rise of inequalities in China was mainly linked to the forceful industrialization process. It was controlled by central planning along the gradual process of modernization. The contrast to the big bang in Russia is startling. The instant opening to the market economy exploded the state and destroyed all public institutions in the 1990s. As a result, the bottom 50% of the population was crushed entirely. Even after the 20 years of reestablishing the verticality of state power from 1998 onwards, real income per capita has undergone a 26% loss over 36 years.

In China real income of the bottom 50% of the population has increased 417% over the same period of the reform launched by Deng Xiaoping and pursued in continuity thereafter. Only Western ideologists and politicians can pretend that China is not democratic. This view is untenable if the criterion of legitimacy is : “what has been done with public power ?” China has moved from a poor, low-income country to the world’s leading emerging economy. Could have it done it with an autocratic repressive power ?

The rising inequality has been largely due to the urban rural divide. In the urban areas of China, the adult population rose from 100 million in 1978 to almost 600 million in 2015. During this same period, the adult rural population remained roughly stable. The income gap between urban and rural China has been growing over time. Urban households earned twice as much income on average as rural households in 1978, but in 2015 they earned 3.5 times as much [17] . It is why the coordinated urban rural development has become a principle of qualitative growth in the new era to reduce the gap, which appears among regions because the process of industrialization has been unequal over the huge territory of the nation.

Figure 1. Top 10% income shares across the world (1980–2016)

Figure 2. Bottom 50% income share (1980-2016)

Table 2. Global income growth and inequality (1980-2016)

(Total cumulative real growth per adult %)

| Income group | China | Europe | India | Russia |

USA- |

World |

| Full population | 831 | 40 | 223 | 34 | 36 | 60 |

| Bottom 50% | 417 | 26 | 107 | -26 | 5 | 94 |

| Middle 40% | 785 | 34 | 112 | 5 | 44 | 43 |

| Top 10% | 1316 | 58 | 469 | 190 | 123 | 70 |

| Top 1% | 1920 | 72 | 857 | 686 | 206 | 101 |

Joint development refers to the strategy of creating or strengthening economic axes to narrow the gaps among regions. The importance of the “Go West” strategy to upgrade Western regions has a straight link with the “One Belt One Road” priority in international development. Western regions will benefit from high-speed railways thrive on processing agricultural products, encouraging cultural tourism and focusing on environmental protection. Central areas have the advantage that they are at the junction of the vertical and horizontal axes of communication. They are building clusters for advanced manufacturing and high-tech industries.

The other pillar for improving inclusiveness, beyond continuous increase in real primary income, is the improvement in social benefits demanded by the expanding middle class. It includes improving health and education on the one hand, and overhauling social welfare on the other hand.

Modernizing and improving education to increase capabilities is a top priority for innovation- led growth. To achieve integrated urban rural development, the Plan has set a target of 95% of child enrollment in compulsory education which will require inclusive pre-school education in rural areas. The educational framework emphasizes vocational education and a major effort to create a modern university system in order to promote higher quality employment to reduce the income gap at the primary level.

A drastic reform of the system of health and medical care is under way with the following orientations : separating hospitals and medicines ; prohibiting hospitals from making a profit on the sale of medicines ; granting legal status to public hospitals ; and increasing their subsidization. Medical costs must be controlled so that the health insurance is affordable and the insurance fund sustainable. Health insurance coverage should reach at least 95% of the rural and urban population by 2020. To guide those sweeping reforms, a National Health Committee has been established, highlighting the paramount importance that the political leadership gives to the ageing problem.

Reform of the social security system is the cornerstone of an inclusive society. Nowadays the system is a hodgepodge of disparate regimes for both retirement and health. The levels of contributions and benefits vary widely from one individual to another and are fragmented geographically. The consequence of this fragmentation is a lack of transferability of risks and rights. Overall, expenditure on health accounts for too much of household budgets and leaves rural retirees and migrants in precarious situation.

President Xi has reasserted the objective of universal coverage. To achieve this, financial mechanisms need to be improved, moderate levels of guarantees provided and administrative responsibilities assigned to administrative levels compatible with the available financial resources. To ensure portability of social rights, the system must become more centralized with responsibilities shifting to central government. The system also must adjust to the ageing population to improve benefits while remaining sustainable. The social security fund will be strengthened by funding transferred from the dividends paid by SOEs to the government as a shareholder.

The main axis of reform addresses population ageing. The retirement age will be extended gradually, with old age activity encouraged, and women’s involvement in the labor force increased, especially in high-competent jobs.

6. Deleveraging and overhauling the financial system

In mid-July 2017, the highest authorities held an important meeting, the 5th national financial work conference [18]. This conference established the Financial Stability and Development Committee of the State Council to strengthen the financial supervisory system. The PBoC’s risk management power was reinforced to prevent the occurrence of systemic financial risk. The new Committee has been assigned the role of enhancing cooperative actions between the PBoC and the financial regulators of banking (CBRC), insurance (CIRC) and securities markets (CSRC). Furthermore the CBRC and the CIRC have merged to crackdown on regulatory arbitrage between the banking and the insurance sectors. Indeed, the dangerous expansion of the shadow banking was largely due to the inconsistency of the guidelines between the regulators, inconsistencies that have fostered regulatory arbitrage, itself generating complexity and opacity that impedes the ability to measure asset quality.

In its latest assessment about China’s financial system stability, the IMF has provided a sober view of the risks and improvements lately achieved [19]. The overall symptom of financial vulnerability is the rise in credit intensity, e.g. the amount of credit needed to generate one more unit of GDP. It has risen steadily, contributing to the large credit gap measured by the overall credit/GDP ratio over its long-run trend. The gap has reached 25%, which points out to significant distress remaining in the financial system from two intertwined processes : credit flows to unprofitable enterprises and obscure financial engineering driven by the proliferation of the shadow banking. Vulnerabilities have been mounting in declining industries generating overcapacities and in the real estate sector.

Nonetheless the financial system has some characters of robustness. Chinese households are little indebted relatively to their accumulated saving. Chinese economic agents have very little foreign debt. Furthermore growth resilience allows room for the authorities to engineer deleveraging. China is not on a razor’s edge. The corporate debt is high at 250% GDP, much higher than emerging market economies, but equivalent of the US and close to UK (270%) and Korea (230%) and, of course, much less than Japan (350%). The authorities have taken steps to address the vulnerabilities and curb the shadow banking.

Deleveraging is imperative for the debt-laden corporate sector anyway. It has been triggered in the private sector by the reduction of fixed asset investment (FAI) in unprofitable industries. It has been underway since 2016 in sectors with the lowest capacity of utilization (coal mining, iron and steel, cement, and other industries transforming primary commodities). It is still robust in automobile, machinery and equipment, and public utility sectors.

For SOEs the government seeks to withdraw the implicit guarantees and clean up zombie firms. For large-size SOEs the method is forcing M&As and injecting equity capital in introducing new investors to develop mixed ownership and improvement in governance. However it will not be enough. Curbing shadow banking will be crucial to containing SOEs’ leverage because shadow banking has become an important funding channel of zombie SOEs.

Shadow banking is very large and complex. To circumvent regulation it has created a large array of financial instruments : wealth management products, trust company products, entrusted loans, bankers’ acceptances, private lending, microfinance loans, trust beneficiary rights, etc…These activities are bank-centric to channel funds from depositors into off- balance sheet product issuances whose proceeds can be channeled into the capital markets and back to the real sectors.

Because the asset quality in the shadow banking is problematic and because it is intertwined with the banking system, shadow banking is a source of contagion risk. Because formal financial institutions cannot identify risk sources, the opacity of shadow banking makes it difficult to manage counterparty risks. Attempts to curb shadow banking via credit tightening in 2013 were unsuccessful because they clashed with the pressure to meet growth targets. Concerted regulatory efforts are needed to close the loopholes and discrepancies in regulation.

It is the role of the new high-level financial regulatory committee established in 2017 to eliminate the financial vulnerabilities transmitted by the shadow banking. The combination of monetary prudence and concerted regulatory efforts has started to bear fruit [20]. Trust loans, entrusted loans and bank acceptances have significantly slowed. New issuance of interbank CDs to finance shadow banking activities of small banks has shrunk. Impulse response functions indicate that one standard-deviation shocks on M2 or total social financing leads to 0.3% impact on GDP growth. Therefore one can presume that current regulation tightening will have limited downward impact on growth.

II China and the world for an inclusive globalization

China’s leadership aims at recovering great power status under the full restoration of the Middle Empire for the 100th anniversary of the foundation of the People’s Republic of China. The ambition is to restructure the world economy according to the mammoth project “One Belt, One Road” (OBOR).

The announcement of the project in the fall of 2013 is a shift in China’s attitude to world politics from Deng’s era, when a low profile in international matters was advocated. In 2014 already the OECD report “Shifting Wealth” pointed out that globalization is entering a new stage, driven by the redeployment of EME growth onto their domestic markets. In Asia this new momentum will integrate the area with the support of massive infrastructure investment. Meanwhile, the US-led financial market-driven brand of capitalism will meet serious obstacles due to the intrinsic inability of markets to finance global public goods like climate, energy security, and ecosystem disruption. It means that global catching up in following Western-style past capitalism is a dead-end.

More recently Trump’s presidency amounts to the destruction by the US of the world order it designed after World War II to secure its benevolent hegemony. From trade to climate, the US has repudiated the international agreement it contributed to promote and lately has moved to outright protectionism. By contrast, in later years China’s State Council has taken initiative to organize a web of trade and financial links in the emerging and developing world, based upon China’s led international financial institutions : the BRIC’s bank, the Silk Road Bank and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB).

However China does not want to overthrow the principle of open multilateral economy, but to work within this principle. Let us understand how financial opening and the move to currency convertibility is managed before assessing the promises of OBOR, since both are matched in the perspective of building a new multilateral world order.

1 Managing financial opening and currency convertibility

Since the 2013 Directives, financial reform in its international dimension has been to promote the Yuan to the status of an international currency by 2020. The government has already been successful in its push to introduce the Yuan in the SDR basket. The logical consequence is the decoupling from the dollar.

The grand design behind the move is the future transformation of the IMS into a multilateral system whose architecture would be based on institutionalized monetary coordination under the auspices of a reformed IMF on the one hand, the upgrading of the SDR as the ultimate reserve asset on the other hand. Under this framework the IMF would become the international lender of last resort, the quota system would be abolished and the issuance of SDR would become endogenous to countercyclical needs in managing the global financial cycle. With an international lender of last resort that is both equitable and open to all countries, the saving that is wasted by many countries in accumulating large amounts of dollar reserves for self-insurance would be reallocated to productive investments.

Such an evolution in the international monetary system is perceived as the monetary basis of a transformation in global finance with public development banks as prominent financiers. According to energy and climate experts, the world should invest $90trns in infrastructure for sustainable development, mostly in developing countries [21] for the next 15 years. The challenge is high because of the colossal lack of infrastructure despite huge amounts of saving. Therefore the world financial system needs to be overhauled [22] . Notably the capacity of public development banks to invest in infrastructures must be massively increased.

As largely observed, financing long-term infrastructure projects involves risks that market finance does not handle. Infrastructure finance requires capital immobilizations during long periods of time, which entail large upfront costs along sequential stages in the process of investing. Those risks are plagued with gross underestimates, which make them difficult to insure. Moreover, the reason for those investments is to produce positive externalities in the economy. Hence their social return is higher than their private financial return. It is why those investments are under produced in the logic of market finance.

Public development banks are the prominent financial actors to fund large size and long maturity projects, which generate positive externalities. They have the mandate to back up such projects. Their capital is owned by financially credible sovereign entities, both national and international. Subsequently they can borrow long on international bond markets at low costs.

Development banks enter the governance of investment projects because they are expert in selecting, evaluating and monitoring complex projects. They are natural partners in the choice of techniques, amounts and localization of infrastructure investments. They can attract other lenders and lever their resources. Their unique characteristics make them the core intermediaries of an alternative model of global finance (table 3).

In emerging market countries the rise to prominence of development banks, linked to central banks, will become drivers of sustainable development. In taking a multilateral dimension, development banks can finance infrastructure projects that integrate whole regions of the world, if they can overcome the pitfalls of coordination. Such a candidate is the Asian International Infrastructure Bank (AIIB) with public shareholders in more than 40 countries. However it is essentially inter Asian with 75% of its capital held by countries in Asia. Others are the Silk Road banks. The national development banks can also play a countercyclical role in preserving financially vulnerable developing countries from external shocks and natural internationalization of the Chinese currency decoupled from the dollar. Correlatively it is a foreign policy advocating the evolution of the international monetary system to multilateralism. Because a system of competing currencies without a commonly accepted international liquidity is unstable, campaigning for a reform of the IMS, whereby the SDR would realize its potential as ultimate international liquidity, is a strategy worth pursuing. Meanwhile China’s government must decide how it proceeds to convertibility, so as to accommodate the long-run objective of a new pattern of globalization and the challenge of the transition.

In doing so, Chinese monetary authorities are confronting a well-known problem in international monetary economics, while choosing a currency regime. It is the famous Mundell’s dilemma [23]. The first best would be the compatibility between fixed exchange rates inducing the stability in capital markets, free capital flows inducing a presumed efficiency in the allocation of world saving, and full autonomy in national monetary policy to pursue relevant domestic objectives.

As the three objectives being incompatible in a world of competing sovereign nations, one of them has to leave. Countries could negotiate compromises and there would be a regime of institutionalized coordination like the Bretton Woods system that essentially accepted capital controls, fixed and infrequently acceptable exchange rates, and autonomy in monetary policy. After the Jamaica Accord of 1976 any common rule has disappeared. When China instituted a single exchange rate and created a central bank to run a unified monetary policy in 1994, the government chose a strict peg on the dollar up to July 2005. Afterwards the government inaugurated a crawling peg, returning to the fixed peg during the financial crisis however. Capital controls remained an essential pillar until the new leadership stated the objective of financial opening. Then Mundell’s dilemma came back with full force.

Table 3. Two models of financial globalization

| Washington consensus | Integration via infrastructure finance |

| + US$ key currency | + SDR multilateral currency |

| Key concept : market efficiency | Key concept : systemic resiliency |

| - Financialization of the firms (shareholder value) - Globalization by capital flows linking all asset markets worldwide via arbitrage and speculation - Intermediation by market making under the dominance of investment banks - Internl LOLR by Fed’s swap network - Developing countries forced to accumulate $ reserve as self-insurance |

- Stakeholder firms as going concerns - Globalization by global public goods and >0 externalities. Finance structured by LT invests - Intermediation by development banks (national and multilateral) - Internl LOLR by IMF’s SDR account - Collective insurance releases saving for productive investment |

| Major shortcoming : inability to finance real LT investments | Major shortcoming : risk of political conflicts in selecting, monitoring and exploiting investment projects |

The long-run solution is clear. China’s ambition requires both free capital flows and independent monetary policy. Therefore a flexible exchange rate regime is the logical consequence, as soon as broad, deep and resilient domestic capital markets have been established and tested. In the meantime, a mix of capital controls should be retained, together with a managed exchange rate regime against a currency basket to preserve the most the autonomy of monetary policy. Nonetheless the stance of monetary policy must be understood by both market participants and observers. It is not only a question of transparency. It is that the monetary authorities can persuade the market that they know how to solve the dilemma on their own and that the decisions of monetary policy, confronting the many shocks that arise in everyday life, are compatible with the stance that has been chosen.

2 OBOR in a new multilateral world order

Coupling a belt that will be linking China to Europe on the ground through Central Asia and a maritime route from China to Mediterranean countries will be OBOR. The goal is to create a platform of economic cooperation between Asia, Africa and Europe. OBOR intends to be a new concept of globalization (table 3). Opposite to the Wall Street model, entirely built upon the domination of finance, OBOR claims multiple forms of interrelationship : political collaboration, infrastructure interconnections, mutual trade, long-term capital flows and mutual understanding between peoples. It hopes to contribute to solve the problems that plague the international community : unequal development, rivalries in political governance and inability to handle the deterioration of common goods.

OBOR initiative provides an overarching framework for China to achieve its economic and strategic goals [24]. Announced by President Xi Jinping in November 2013 at the third plenum of the CPC, OBOR is an integral part of the new era. Its development will cover the entire period between 2013 and 2050 in three phases : mobilization (2013-2016), planning (2016-2021), and implementation (2021-2049) [25]. OBOR brings infrastructure, new trade route and better connectivity between China and Europe. A Belt and Road forum took place in Beijing in May 2017 ; 30 heads of State attended the forum along representatives of 100 countries and 70 international organizations [26] . Countries of South-East and Central Asia were heavily represented. In his address to that conference, President Xi urged delegations to reject protectionism and embrace the new China-driven concept of globalization, more inclusive and more equitable in providing mutual benefits.

OBOR opens opportunities to recipient countries that are infrastructure-constrained, because their lack of public goods is undermining their development. Conversely it is the right platform to push China’s soft power across Eurasia with strengthening economic linkages through trade, capital flows and construction deals. The Asian Development Bank (ADB) estimates that OBOR countries need to invest $22.6trn in infrastructure from 2016 to 2030 ($1.6trn yearly) in electricity generation, transport and telecom to drive up growth. Conversely, long-term investments generate potential growth for sustaining future debt- servicing capability.

Apart from infrastructure investment, Chinese digital companies exhibit increasing interest in investing into OBOR regions as well. Such investment and economic activities can help those regions to leapfrog in their developmental stages and potentially embrace a greener trajectory of development as well.

OBOR funding is reliant on China-based institutions (80% of total in the mobilization phase until 2016) and an array of multilateral financial institutions (AIIB, Silk Road Fund, New Development Bank for BRICS, ADB and World Bank). OBOR provides an opportunity to internationalize the renminbi as a vehicle currency in cross-border trade settlements and in local currency swap agreements. As a financing currency it can rest on Hong Kong which will become a major financing hub for OBOR.

The OBOR initiative will succeed with Asian integration, since China will become the first world economic power before 2030. It is why OBOR is complemented by the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). The negotiation of RCEP has been boosted by Trump’s rebuke of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). RCEP will be an economic partnership agreement covering the 10 ASEAN countries plus 6 other countries (China, India, Korea, Japan, Australia and New Zealand). The agreement on tariffs is a work in progress that is due to be completed and signed in November 2018. RCEP +OBOR make a formidable tool to retaliate against US protectionism. Aggressive US actions will strengthen China’s leadership in Asia, while the rebound effect of protectionist actions against China will hurt US interests, considering how high US investments are in China. By eliminating trade tariffs within regional supply chains, RCEP will help regional manufacturing for a more compact regional industrial structure.

Conclusion : China and the world.

In 1950 China was by far the poorest country of the world, with GDP per capita 4.6% of the US according to Maddison (OECD). In 1990 it reached 6.7%, then the catching-up has been outstanding : 12.8% in 2000 and close to 25% in 2015. China is well on its way to socialist modernization.

The transformation of China’s economy in the next 20 years will change the pattern of globalization. It will take a new course under the imperative challenge of inclusive and sustainable growth. In Asia this new momentum will integrate the area with the support of massive infrastructure investment. Meanwhile the US-led, financial market-driven brand of capitalism will meet serious obstacles due to the intrinsic inability of markets to finance global public goods, like climate, energy security, and ecosystem disruption. 21st century capitalism will not create sustainable growth regimes without socio-political innovations from multiple regions of the world. To achieve sustainable growth, the global financial system must be transformed in the direction of long-term financing.

China’s assertiveness in world markets and world politics stems from this huge incipient regime change. China does not want to overthrow the principle of open multilateral economy, but to work to improve it with its own characteristics. China’s collective leadership wants to restore back the historical central role of the Chinese Empire in Asia. Therefore they want the country to be entirely reunited.

China is more than a nation state. It is a millenary civilization that has created the institutions of a unitary imperial state. China has no desire and no need for global hegemony, because her founding culture does not pretend to carry out universal values. With the rest of the world, China wants to develop economic, financial, technological and cultural relationships and cooperate politically to secure the global public goods on which our common security depends.

Bibliography

Aglietta M. and Bai G. (2012), China’s development : capitalism and empire, Routledge

Aglietta M. and Bai G (2014), China’s roadmap to harmonious society, CEPII policy brief, n°3, May

Alvaredo F., Chancel L., Piketty T., Saez E. and Zucman G.(2017), Global Inequality Report, WID.world Working Paper Series (No. 2017/20)

Dcorukhkar S. and Le Xia (2017), “China one belt, one road : progress and prospects”, China Economic Watch, BBVA Research, November

Garcia Herrero A. (2017), « A stellar global economy in 2018 », Natixis Beyond Banking, December

Green F .and Stern N. (2015), « China’s new normal :structural change, better growth and peak emissions”, policy brief, University of Leeds and LSE, June.

Hsu A. (2017), “the environmental horizon : still murky”, China Economic Quarterly Review, vol.21, n°4, December.

IMF Country Report (2017) n°17/358, People’s Republic of China : Financial System Stability Assessment, December

International Energy Agency (2017), World Energy Outlook : China, November 14th

Jinyue Dong, Huang B. and Le Xia (2017), « taming China’s Shadow Banking Sector”, BBVA Research, August 22.

Jinyue Dong, Ortiz A .and Le Xia (2018), « China from miracle to great moderation : potential GDP estimation of China”, BBVA research, China Economic Watch, January.1

Kroeber A.(2017), « a good few decades, but not a Chinese century », China Economic Quarterly, vol 21, N°4, December.

McKinsey Global Institute report (2017), « Digital China : powering the economy to global competitiveness », December.

Miller T. (2017), « Belt and Road to leadership », China Economic Quarterly Review, vol.21, n°2, June

Scholten D. ed. (2018), The Geopolitics of Renewables, Springer

Stern N. (2015), « keeping the climate-finance promise », Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change, LSE, November 12.

S.E.Zhai Jun (2017), « l’avenir des relations franco-chinoises », Institut Diderot, Les Carnets des Dialogues du Matin, Juin.

Umehara N. (2017), overview of the 5th National Financial Work Conference : China seeks for financial stability and development, newsletter of the Institute for International Monetary Affairs, n° 15.

UNCTAD (2015), « Long-Term International Finance for Development : challenges and possibilities”, Report chap.VI.

Zhang Weiwei (2018) « How China made it », The Economist, March 10-16.

A lire en complément :

« La Chine développe un capitalisme qui ouvre une voie originale vers le XXIe siècle »

Le Monde du 21 avril 2018

« Michel Aglietta penseur des limites du capitalisme »

Le Monde du 3 mai 2018

Notes

[1] Michel Aglietta is emeritus professor in economics at University Paris Nanterre and consultant at Cepii and France Strategy

[2] Guo Bai is Ph.D. graduate at HEC Paris, Lecturer of Strategy at China Europe International Business School (CEIBS), and research fellow at the China Institute, Fudan University, Shanghai.

[3] A. Kroeber, « a good few decades, but not a Chinese century », in China Economic Quarterly, vol 21, N°4, December 2017.

[4] Zhang Weiwei (director of the China Institute at Fudan University, Shanghai), « How China made it », The Economist, March 10-16, 2018.

[5] BBVA Outlook, first quarter 2018

[6] A.Garcia Herrero, « A stellar global economy in 2018 », Natixis Beyond Banking, December 2017

[7] Service économique régional du Trésor à Pékin (2017), Bulletin de Statistiques Economiques, 4° trimestre.

[8] Jinyue Dong, Alvaro Ortiz and Le Xia, « China from miracle to great moderation : potential GDP estimation of China, BBVA research, China Economic Watch, January 2018.

[9] A unicorn is a start-up whose assets are valued at 1 billion or over

[10] Boston Consulting Group report, « fast and Furious : Chinese unicorns to overtake American counterparts, September 18, 2017, made in collaboration with the research divisions of Alibaba, Baidu and Didi.

[11] McKinsey Global Institute report, « Digital China : powering the economy to global competitiveness », December 2017.

[12] Angel Hsu, “the environmental horizon : still murky”, China Economic Quarterly Review, vol.21, n°4, December 2017, pp.55-60.

[13] D.Scholten ed. (2018), The Geopolitics of Renewables, Springer

[14] International Energy Agency (2017), World Energy Outlook 2017 : China, November 14th

[15] F.Green and N.Stern, « China’s new normal :structural change, better growth and peak emissions”, policy brief, University of Leeds and LSE, June 2015.

[16] Facundo Alvaredo, Lucas Chancel, Thomas Piketty, Emmanuel Saez, and Gabriel Zucman (2017), Global inequality Report, WID.world Working Paper Series (No. 2017/20)

[17] Thomas Piketty, Li Yang, and Gabriel Zucman (2017), “Capital Accumulation, Private Property and Rising Inequality in China, 1978–2015,” WID.world Working Paper Series (No. 2017/6).

[18] Naoki Umehara, overview of the 5th National Financial Work Conference : China seeks for financial stability and development, newsletter of the Institute for International Monetary Affairs, n° 15, 2017.

[19] IMF Country Report, n°17/358, People’s Republic of China : Financial System Stability Assessment, December 2017

[20] Jinyue Dong, Bbetty Huang and le Xia, « taming China’s Shadow Banking Sector”, BBVA Research, August 22, 2017

[21] Stern N. (2015), « keeping the climate-finance promise », Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change, LSE, November 12.

[22] UNCTAD (2015), « Long-Term International Finance for Development : challenges and possibilities”, chap.VI, 2015 Report, pp.153-179

[23] Mundell’s impossibility theorem is exposed in his book International Economics, Mac Millan (1968).

[24] Tom Miller (2017), « Belt and Road to leadership », China Economic Quarterly Review, vol.21, n°2, June.

[25] Sumedh Dcorukhkar and Le Xia (2017), “China one belt, one road : progress and prospects”, China Economic Watch, BBVA Research, November.

[26] S.E.Zhai Jun, « l’avenir des relations franco-chinoises », Institut Diderot, Les Carnets des Dialogues du Matin, Juin 2017.

ERYTHRÉE : LEVER LES BRAS POUR EXISTER. Mathieu ROUBY

LA CHINE ET SES VOISINS : ENTRE PARTENAIRE ET HÉGÉMON. Barthélémy COURMONT et Vivien LEMAIRE

L’ÉCRIVAIN et le SAVANT : COMPRENDRE LE BASCULEMENT EST-ASIATIQUE. Christophe GAUDIN

BRÉSIL 2022, CONJONCTURE ET FONDAMENTAUX. Par Hervé THÉRY

« PRESIDENCE ALLEMANDE DU CONSEIL DE L’UE : QUEL BILAN GEOPOLITIQUE ? " Par Paul MAURICE

LES ELECTIONS PRESIDENTIELLES AMÉRICAINES DE 2020 : UN RETOUR A LA NORMALE ? PAR CHRISTIAN MONTÈS

LES PRÉREQUIS D’UNE SOUVERAINETÉ ECONOMIQUE RETROUVÉE. Par Laurent IZARD

ÉTATS-UNIS : DEMANTELER LES POLICES ? PAR DIDIER COMBEAU

LE PARADOXE DE LA CONSOMMATION ET LA SORTIE DE CRISE EN CHINE. PAR J.R. CHAPONNIERE

CHINE. LES CHEMINS DE LA PUISSANCE

GUERRE ECONOMIQUE et STRATEGIE INDUSTRIELLE nationale, européenne. Intervention d’ A. MONTEBOURG

LES GRANDS PROJETS D’INFRASTRUCTURES DE TRANSPORT SONT-ILS FINIS ? R. Gerardi

LES ENTREPRISES FER DE LANCE DU TRUMPISME...

L’ELECTION D’UN POPULISTE à la tête des ETATS-UNIS. Eléments d’interprétation d’un géographe

Conférence d´Elie Cohen : Décrochage et rebond industriel (26 février 2015)

Conférence de Guillaume Duval : Made in Germany (12 décembre 2013)

GEOPOWEB, LIRE LE MONDE EN TROIS DIMENSIONS (Géopolitique, Géoéconomie, Philosophie politique). Mondialisation « à front renversé » : politiques d’endiguement, lois extraterritoriales, guerres hybrides, sécurité stratégique...

GEOPOWEB, LIRE LE MONDE EN TROIS DIMENSIONS (Géopolitique, Géoéconomie, Philosophie politique). Mondialisation « à front renversé » : politiques d’endiguement, lois extraterritoriales, guerres hybrides, sécurité stratégique...

LA BATAILLE DES BATTERIES ÉLECTRIQUES NE FAIT QUE COMMENCER. Par Stéphane LAUER

LA BATAILLE DES BATTERIES ÉLECTRIQUES NE FAIT QUE COMMENCER. Par Stéphane LAUER